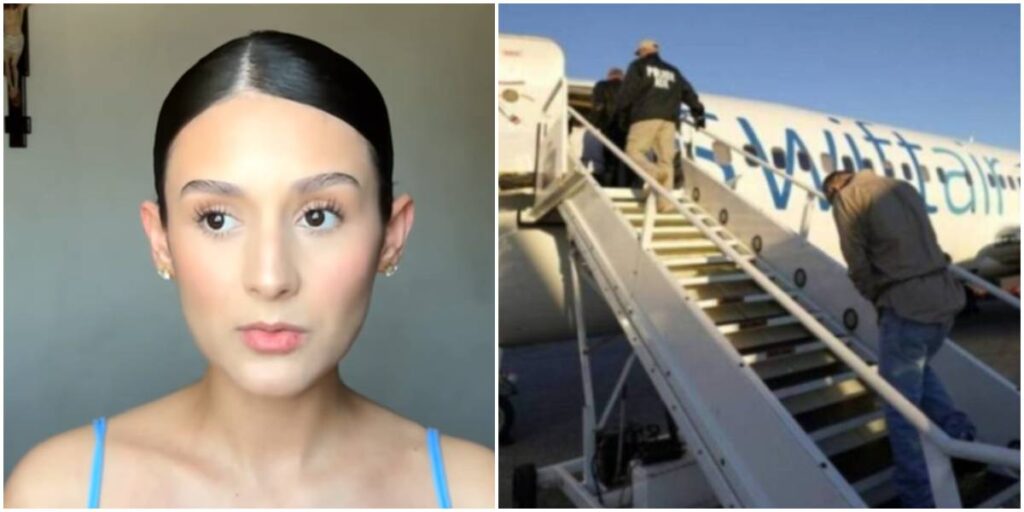

Con tan solo 23 años, Yokari Villagómez fue obligada a tomar una de las decisiones más difíciles de su vida: abandonar voluntariamente Estados Unidos, el país donde creció, estudió, se casó y al que consideraba su verdadero hogar. Su historia, relatada con crudeza, refleja la angustia de miles de migrantes atrapados en un limbo legal y emocional, víctimas de un sistema migratorio complejo, saturado y, muchas veces, indiferente.

Una vida construida desde niña

Yokari llegó a Estados Unidos cuando tenía apenas 11 años, cruzando la frontera desde México con su familia. Como muchos otros menores migrantes, se adaptó rápidamente a su nueva realidad: aprendió inglés, se graduó de la secundaria y luego estudió diseño de modas. Años más tarde, contrajo matrimonio con un ciudadano estadounidense y se estableció en California, donde vivía de forma tranquila y estable.

A pesar de estar plenamente integrada a la vida estadounidense, su estatus migratorio seguía siendo irregular. En lugar de ser canalizada hacia una vía de regularización por su matrimonio, su proceso legal fue entorpecido por múltiples errores cometidos por su abogado, quien no presentó a tiempo la documentación correspondiente. Esa omisión sellaría su destino.

Detenida sin explicación, tratada como criminal

Un día, sin previo aviso, agentes migratorios la detuvieron y la trasladaron a un centro de detención. No le permitieron comunicarse con su esposo, y fue esposada como si se tratara de una delincuente. “No me dieron la oportunidad de hablar con mi esposo. Fui esposada sin explicación y llevada a un centro de detención”, dijo la joven quien no tenía antecedentes penales ni había cometido infracción alguna, salvo la de haber permanecido sin papeles en el país durante su infancia y juventud.

Durante su encierro, Yokari denunció haber sufrido condiciones inhumanas. Una fractura facial causada por una caída no fue tratada médicamente y la alimentación era deficiente. El aislamiento, la incertidumbre y el miedo deterioraron rápidamente su salud mental. “Ahí dentro, el tiempo se detiene, pierdes la noción de quién eres, y te sientes desechada”, relató con angustia.

La decisión extrema: autodeportarse

Tras semanas de reclusión y ante la falta de respuestas claras por parte de las autoridades migratorias, Yokari optó por la única vía que le ofrecía algún control sobre su destino: solicitar su autodeportación. Aunque esta alternativa ha sido presentada por ICE y CBP como una opción “voluntaria” frente a la deportación forzada, en la práctica suele ser la única salida posible cuando los migrantes no tienen recursos para enfrentar procesos largos, inciertos y costosos.

Su salida del país se concretó el 25 de junio de 2025. Atrás quedaron su esposo, su carrera profesional incipiente y más de una década de vida. El regreso a México, un país que apenas recuerda de su niñez, fue un golpe emocional profundo. “Fue una ayuda invaluable, ya que las autoridades de inmigración me estaban poniendo trabas para irme. El consulado mexicano fue fundamental para que mi solicitud fuera procesada”, contó.

Tras su deportación a Rosario, Baja California la muchacha agradeció recibir una atención médica, sin embargo, no logra rebasar la amarga experiencia. “Es difícil aceptar que todo lo que soñé en los EEUU se quedó allá. Perdí la oportunidad de completar mi carrera, y ahora tengo que empezar de nuevo”, afirmó.

Una realidad que se repite

El caso de Yokari no es único. De acuerdo con cifras recientes, más de 13.000 migrantes se han autodeportado en lo que va de 2025, la mayoría tras largos periodos de detención o tras enfrentar procesos legales fallidos. Aunque las autoridades alegan que este mecanismo es una opción humanitaria, defensores de los derechos de los migrantes señalan que en muchos casos se trata de una forma de coacción bajo condiciones de encierro y desesperación.

Además, los reportes sobre el trato que reciben los detenidos en centros migratorios, especialmente aquellos sin antecedentes penales, han sido objeto de crecientes denuncias. Casos de negligencia médica, hacinamiento, restricciones de comunicación y violencia institucional han sido documentados por organizaciones como ACLU y Human Rights Watch.

Un sistema en crisis

La experiencia de Villagómez revela no solo los errores individuales en su caso legal, sino también las profundas fallas del sistema de inmigración de EE. UU., que no logra ofrecer respuestas eficientes a personas que han vivido durante años de forma pacífica y productiva en el país. “¿De qué sirve integrarte, estudiar, casarte, cumplir las reglas, si un error burocrático te condena a perderlo todo?”, se preguntó.

Mientras tanto, la presión sobre el gobierno estadounidense aumenta. Las deportaciones han crecido, y también las detenciones de migrantes con documentos como el I-220A, lo que ha generado temor incluso entre aquellos que han estado cooperando con las autoridades. En este contexto, las autodeportaciones se han convertido en una vía de escape para muchos, pero a un costo emocional altísimo.

“No me fui por elección, me fui porque el sistema me empujó”

Yokari Villagómez hoy intenta rehacer su vida en México. Lejos de su esposo, de sus amistades y de todo lo que conocía, enfrenta el desafío de empezar de nuevo. Aun así, mantiene la esperanza de que algún día pueda regresar legalmente al país que siente como suyo. Su historia es un recordatorio poderoso del costo humano de las políticas migratorias actuales, y de la urgencia de una reforma migratoria integral en Estados Unidos.